The Porch is excited to welcome Memphis-based writer & illustrator Martha Park to Nashville as part of its Visiting Writers Series in Spring 2025. In advance of Park's visit, Porch cofounder Susannah Felts interviewed Park for her Substack, FIELD TRIP. We're cross-posting the piece below, and we hope that you'll join us for conversation and writing with Park on May 15. —Ed.

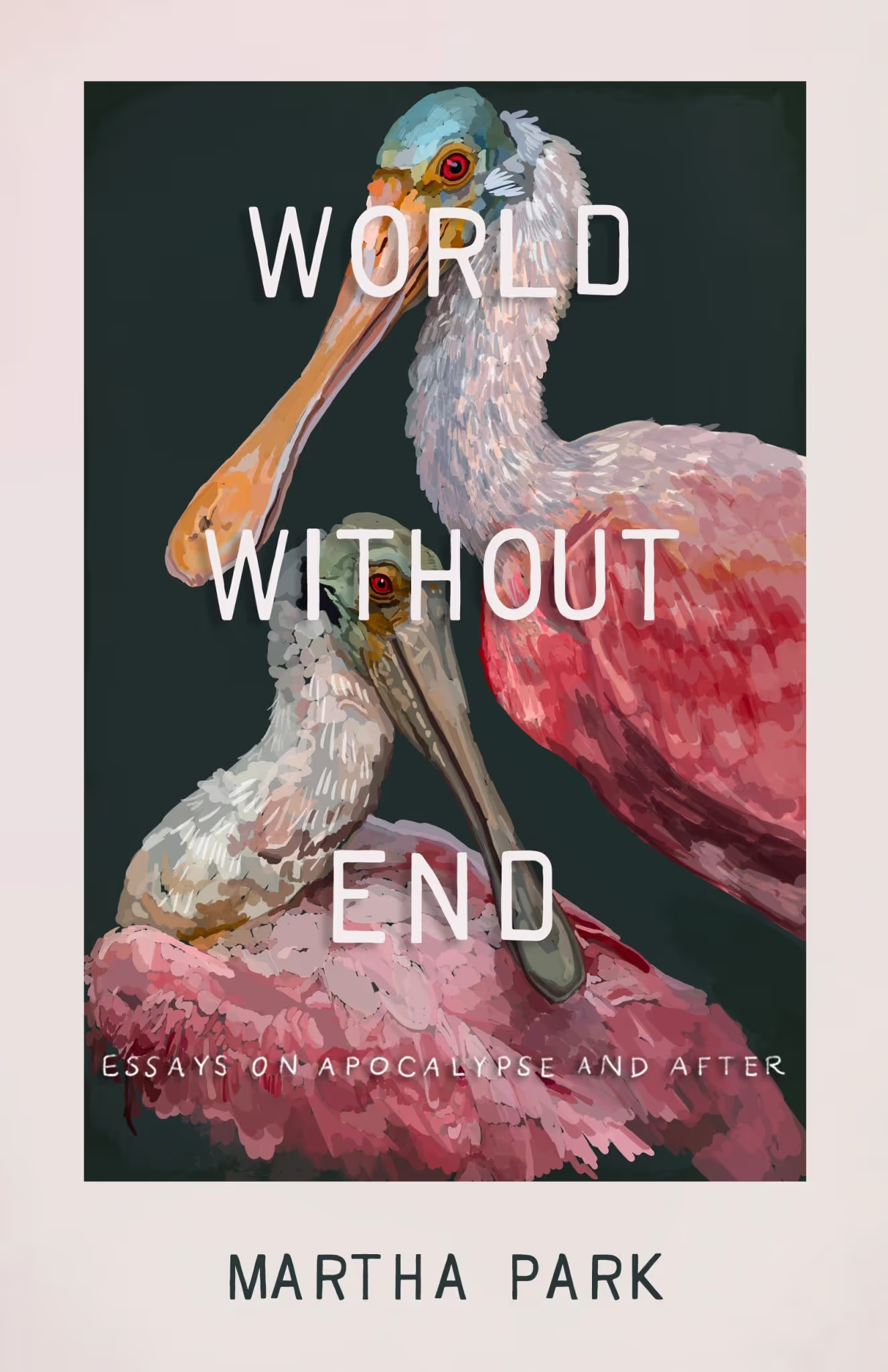

I have a kind of crush on anyone who can write AND draw well. It’s always exciting to me to see how an artist combines image and text to tell a story—to see what emerges as illustrated image and what remains in the symbolic language of ye olde alphabet. Enter Martha Park, author of the just-published World Without End: Essays on Apocalypse and After (Hub City Press). The book examines “expressions of faith and doubt,” as Park puts it below, and takes readers from a Noah’s Ark replica in Kentucky to the woodlands of Florida (I loved learning about the torreya tree!) to natural burial sites of the Southeast, Park gently asking questions of herself along the way. It’s a great example of how you can take a personal experience and broaden it to explore others’ lives, historical figures, adjacent places, and controversies that, perhaps at first glance, seem to have little to do with you. In my years of teaching, I find that so many want to write personal essays, but struggle to situate their stories in a bigger picture. Martha Park succeeds at just that. I hope aspiring essayists and memoirists will read this book not just for its exploration of Hot Topics (hey, climate change!) but for its thoughtful blending of public and private.

Also, it’s a Southern book through and through. Love to see it! When the publication announcement came out, I felt a little thrill. Here was someone, a contemporary someone, in my home region, writing directly and about that region! Not even just from my region, but from my home state of Tennessee! (Honestly, there just isn’t enough of this.)

I first became aware of Park as an illustrator thanks to Instagram, which did the good work it can, in fact, do (I don’t recall exactly through what mutual connection we became connected.) I’ve smashed the like button many, many times for her gorgeous drawings and illustrations for magazine covers. Do I hope we can feature her someday in SWING? Umm, yes. Putting that here to help manifest it.

Park hails from Memphis, Tennessee, and received an MFA from the Jackson Center for Creative Writing at Hollins University, and was the Spring 2016 Philip Roth Writer-in-Residence at Bucknell University’s Stadler Center for Poetry. She has received fellowships from the Religion & Environment Story Project and the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts.

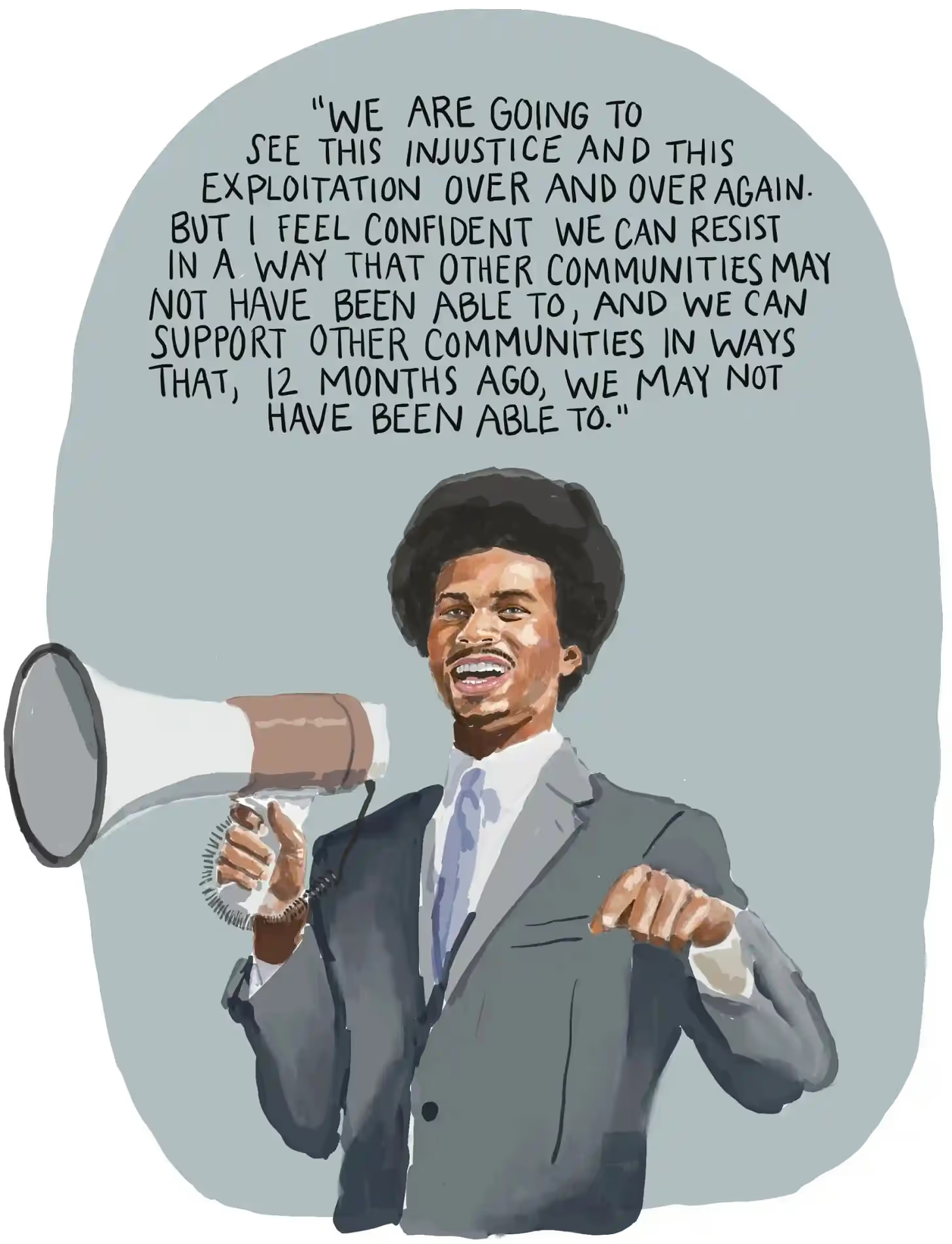

Her collaborative illustrated journalism has been supported by grants from the Economic Hardship Reporting Project. “Washed Away,” a comic about Kentucky landslides made with environmental journalist Austyn Gaffney, has been recognized with an EPPY Award for Best use of Data/Infographics and was a finalist for the Institute for Nonprofit News’ Insight Award for Visual Journalism.

Martha’s writing, graphic essays, and illustrations have appeared in Orion, Oxford American, The Guardian, Guernica, The Bitter Southerner, Granta, Ecotone, ProPublica, and elsewhere.

It is an honor and delight to feature her here today.

The South is the whole thing. Where I came from, where I’m headed. The place I’m trying to know and love better. All the essays in the book are inspired by and indebted to this place.

My publishers suggested I add illustrations, and invited me to create the artwork for the cover. I don’t have any other experience to compare it to, but I imagine this is one of the joys of working with an independent press. They expanded my vision of the book. I thought I’d need to compartmentalize the book, or myself, and that including my visual art work would complicate things too much. It was such a gift to have publishers invite my whole self into the work.

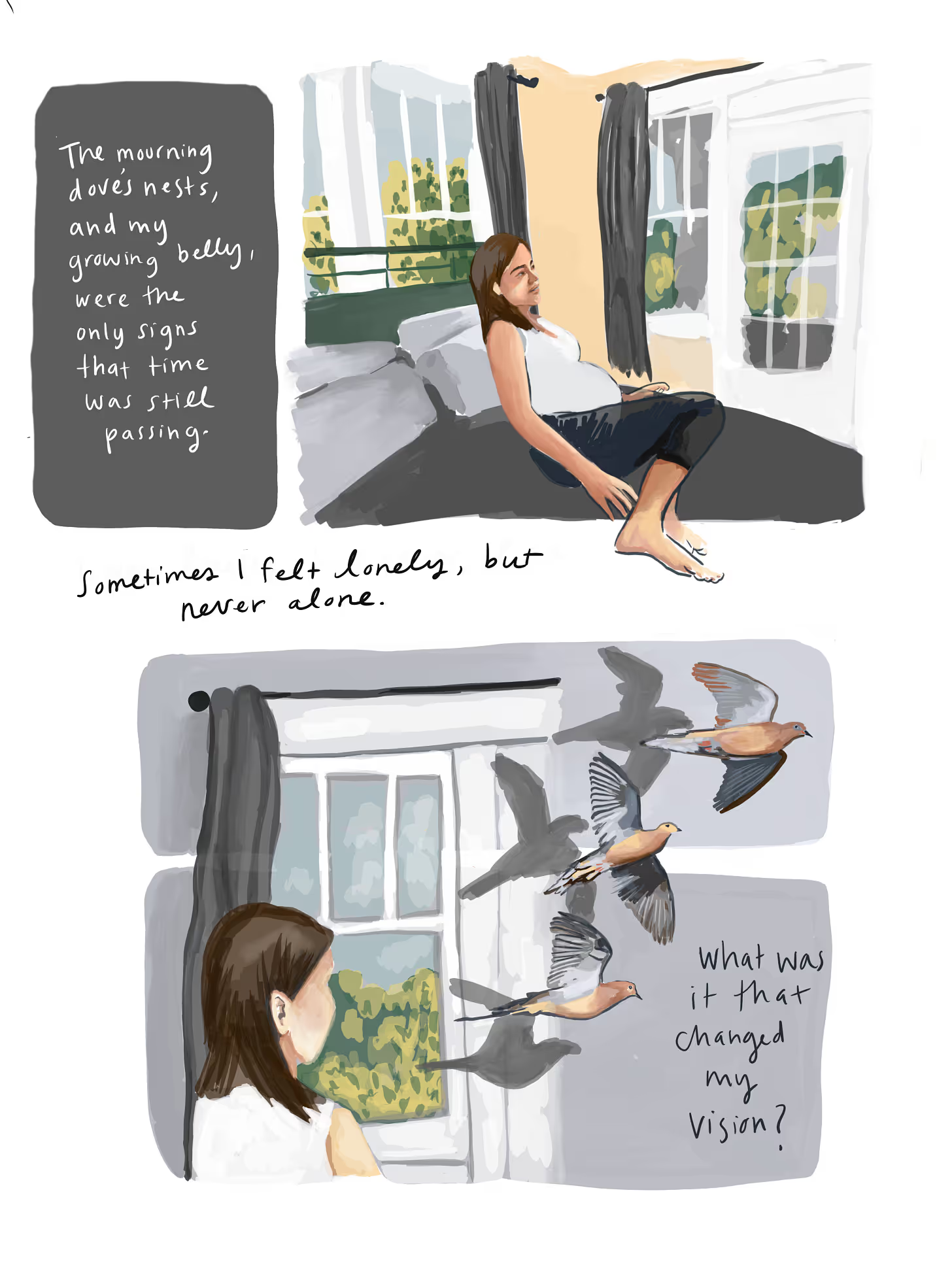

I wrote these essays over the course of ten years. At first I thought I was writing more of a memoir about attending church for my dad’s last year in the pulpit. But I discovered very quickly that I’m not a memoirist. I didn’t feel like I had that much to say about my own experience--I couldn’t find my way into it by myself. So I started writing about other people, other places, other expressions of faith and doubt. I found that writing in conversation with other people and other stories broadened my understanding of myself and my own story and allowed me to reach insights and explore questions I wouldn’t have found on my own. So the book became a mix of personal essays and reported essays, and I love the way they speak to and complicate each other.

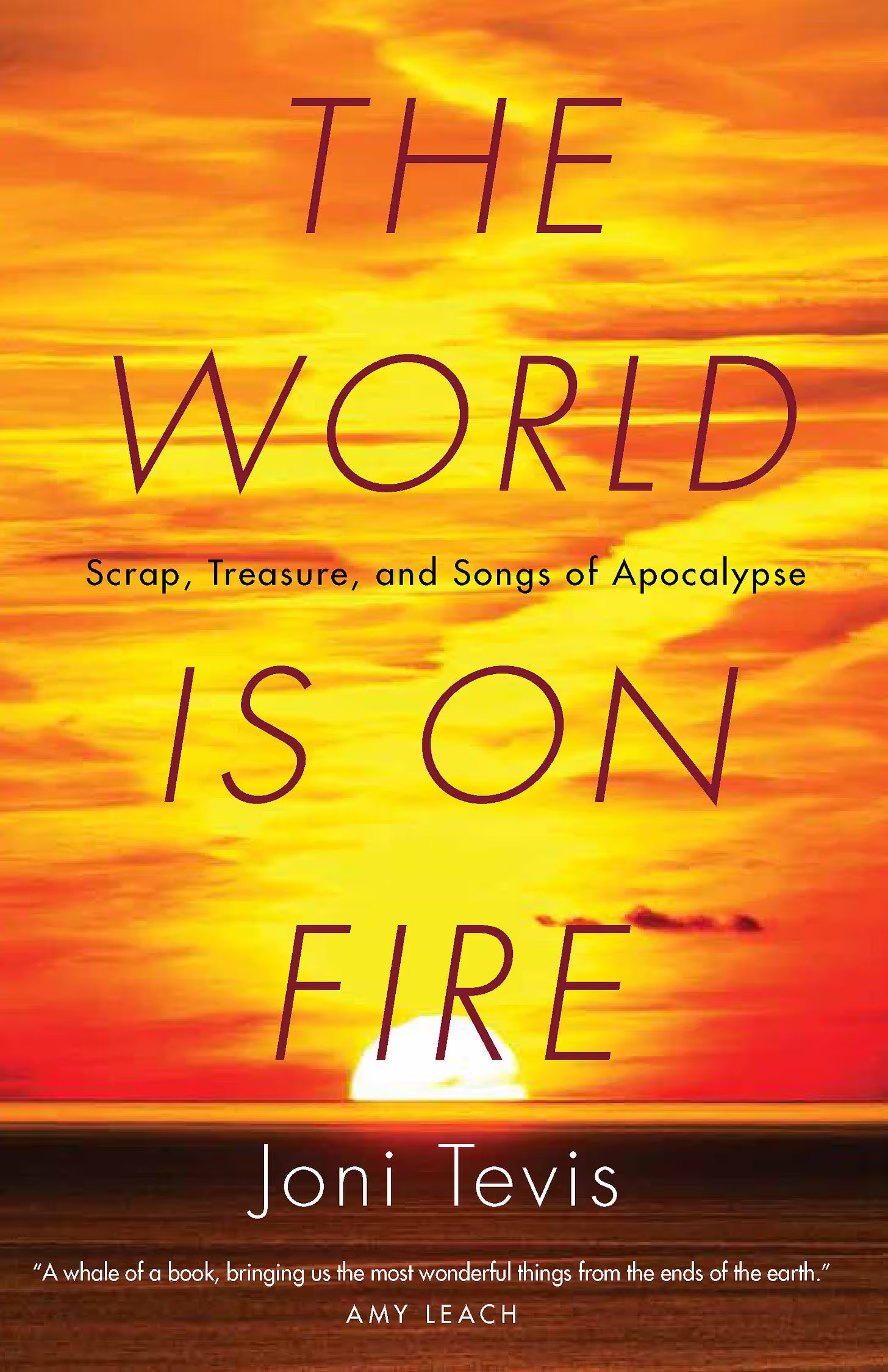

I’m a Joni Tevis super-fan. Her book The World is on Fire: Scrap, Treasure, and Songs of Apocalypse is one of my forever-favorite books. But there are some lines from the end of her book The Wet Collection that describe my mother’s accent—her precise pronunciation of specific letters and words—so perfectly, I feel this deep recognition, a full-body frisson, every time I read it: “My password is any word containing ‘oi,’ vowels tucked between supple consonants…Coil sounds like coal, foil like foal. When I am home, these words smooth my path. But I have been away so long.…Let my slow speech give me away. My soil sounds like soul; my home will ever fill my mouth.”

As a kid, I was definitely a tomboy: bare feet, bowl cut, nearly feral, outside most of the time. Particularly proud of the calluses on my feet. By the time I was in high school, I liked wearing dresses, keeping my hair long. But it felt a little like a costume. Still does. I’m never more anxious than I am around Southern women who really know how to do the whole shebang. It’s a certain language I’ve never felt able to speak.

A childhood memory for me that is particularly hard-wired is from preschool. When my friends played house, they jostled over who would get to play the mommy, who would play the baby or the big sister. But I always wanted to be the “house racoon” (whatever that means), pretending to rummage through the trash. Growing up, I always identified as a tomboy, a Harriet-the-Spy-wannabe, a house raccoon. Still do.

I feel pretty fully Southern. I guess if anything, after a spell of years living in and near the Blue Ridge Mountains, I feel more drawn to a different version of the South than the one where I grew up and currently live. I’ve been back in Memphis for seven years now, but am always missing the seasons and the deeper sense of connection to the natural world that I experienced in North Carolina and Virginia.

Any of the small United Methodist churches my father served over the course of my life still feel intimately, intensely, like home.

a. You dislike

b. You love, or

c. That you’ve used in your work

My mother’s side of the family passed down “good night” as an exclamation. I love the way the words stretch; the number of syllables conveying the depth of your surprise or dismay. She also says “woppy-jawed,” which is a personal favorite. When my paternal grandmother was surprised or frustrated she would say “I swonny,” instead of “I swear,” which I weirdly don’t say aloud but which pops into my mind, often, and feels like a little communion with her spirit. When I was in college in Ohio, people made fun of me when I said “y’all”--but it’s caught on now, as it ought to. It’s such an elegant, efficient, inclusive word.

I like the feeling of having a deep connection to a specific place, simply by virtue of time and affection. Every day is a chance to time travel, to revisit past selves and old haunts, to feel my mind swerve, in response to a certain smell in the air after a rain or the light shifting in the trees, to a memory of my grandmother, or a first love, or a summer night driving around aimlessly with a friend I haven’t seen in years. No place is anonymous: there are neighborhoods--individual streets--that I don’t know very well but where my grandmother was a beloved neighbor; churches I’ve never stepped inside but which I know were full of people, long-gone now, who took care of my dad when his own father died; driving by a hospital or grocery store or a cemetery is an opportunity to be reminded of an old wound, or some small miracle, or the way generations of people have lived and died here and rooted me to this place. It all gives me a sense of coherence.

When I was a kid our church youth group would go on “work trips” volunteering around the South. These were non-proselytizing, purely an effort on our parents’ parts to get us out of the house and involved in community service. One summer we went to Pass Christian, Mississippi, which had been very nearly destroyed by Hurricane Katrina. I remember the human and environmental devastation, our totally inadequate adolescent efforts to repair a home that had been left to rot for months while its owners, a couple who were caught mid-divorce when the storm hit, fought over whether the house should be repaired or torn down. I remember sensing the weight of what the South was up against: the storms, the sea level rise, the governmental bureaucracy, our own fickle, tormented hearts.

Another summer, we traveled to a town on the edge of a mountain in West Virginia which locals called “the end of the world.” We were there to repair an old woman’s roof and repaint her house, which had previously been painted with discarded yellow and white highway paint. This was the kind of small town where there’s no trash service, but instead of hauling their trash out, neighbors had filled an abandoned house--across the street from this little old lady’s house--with trash, floor to ceiling. We spent a week or whatever painting her house, again just feeling inadequate and stupid in the face of the amount of more substantive support and care this woman and her neighbors should have had, instead of us. At the end of the week she invited us into her house to pray for us. She anointed each of our heads, using a jar of olive oil from her kitchen. It was a kind of formative sacred experience for me. I can still travel through her house, her street, in my mind. I wonder all the time about her.