As we eagerly await US Poet Laureate Ada Limón's visit to Nashville on May 3-4, we're happy to share an interview with her conducted by Sara Beth West for Humanities Tennessee's Chapter 16, a community of Tennessee writers, readers, and passersby. Read the beginning here, then click through for the full piece.

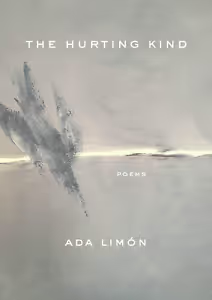

In her career as a poet, Ada Limón has been much celebrated. Her 2018 collection, The Carrying, won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Poetry, and her work has been nominated for the National Book Award and Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award as well. She received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2020 and was named the 24th U.S. Poet Laureate in 2022. Her latest collection, The Hurting Kind, has been lauded for the way it blends the mysterious with the ordinary, the everyday with the exceptional. Her work is known for being accessible while still elevating readers, urging them into wonder and curiosity.

Limón’s poems are grounded in the physical world, delighting in robin and groundhog, horse and grackle and fox. And always there is a turn, an unexpected insight that brings together disparate things, creating a new and vital whole. The Hurting Kind draws much on the isolation and forced quietude of the COVID-19 lockdown period, but it emerges triumphant, full of life and light and shot through with hope. Her work serves as a witness and invites readers to join in the act of seeing and being seen, an idea explored in “Sanctuary,” which concludes, “The great eye // of the world is both gaze / and gloss. To be swallowed / by being seen. A dream. // To be made whole / by being not a witness, / but witnessed.”

Originally from Sonoma, California, Limón now makes her home in Lexington, Kentucky. She recently spoke with Chapter 16 by phone. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Chapter 16: How has being named poet laureate changed things for you? Are you still able to write with the same frequency or focus? Or is this a season to celebrate poetry more generally?

Ada Limón: I think it’s interesting because making poetry is inherently private on so many levels. And this is such a public role. So there is this part of me that always has to negotiate when it is time to be public, and when it’s time to be private. That was there already, of course, but this has elevated it and heightened it to a new level. There’s a part of me that sometimes gets a little divided and has to figure out when I get to be the artist, and when I get to be the performing artist, which are different things.

Overall it has really been impressed upon me how many people not only need poetry right now but are writing poetry, some people for the very first time. I think that during the isolation and grief of the chaos of the early days of the pandemic, people were looking for ways to reach out and connect. Much like bird watching became so essential to so many of us, I feel like poetry did, too. So I’m going around, and it really feels like there is a surge of energy around poetry right now that I haven’t seen before, and it feels very necessary. People are really looking to connect, and they’re looking to get healed, and it’s really powerful. It’s very emotional.

Chapter 16: The idea of making music or singing crops up frequently in your work. For example, “The Leash” asks, “Isn’t there still something singing?” and the epigraph to The Hurting Kind says, “Sing as if nothing were wrong. / Nothing is wrong.” I can’t help but wonder: Is singing “as if nothing were wrong” another definition of poetry? Do you see yourself as making music with your poems?

Limón: Unlike the incredible musicians we have both in Tennessee and Kentucky as well as all over the world, poets don’t get to work with all the music. We don’t get to have the guitarist and the bass line and the drums. We have to make all of that on the page. And so the whole poem has to be the song, and it has to have all the instruments and all the harmonies and the melodies. And I feel like when I’m writing, I’m aware of that. There is a type of singing that’s happening, and the singing is spoken, of course. But there is a level in which the musicality is high, especially in the work I’m most drawn to.

The other part of that is there’s a way that singing calms us, like the way you sing to a child or the way you come into communion or in community with other people. Singing together is such a powerful bond, and I think that way of making music on the page and offering something back to the world is a kind of rebellion, but also a celebration at the same time — a rebellion against everything that is suffering. But then also, a celebration of everything that’s alive and whole.

All those things are very much a part of not only who I am as a human, but who I am as an artist. You know, I always laugh because I can’t listen to music when I write, because I have to make my own. I don’t understand the idea of background music. If I’m listening to music, I’m either dancing or singing along, or I’m in it, I’m in that world. I always have to have complete silence when I write because of that. Music is very powerful and emotional for me.

Continue on to the full interview here. Thanks for sharing this with us, Chapter 16 and Sara Beth West!