Christian J. Collier is a Black, Southern writer, arts organizer, and teaching artist. He is the author of Greater Ghost (Four Way Books, 2024), and the chapbook The Gleaming of the Blade, the 2021 Editors’ Selection from Bull City Press. His work has appeared in The Atlantic, POETRY, December, and elsewhere.

Fellow poet Joy Priest has described Christian as a Black Surrealist. An imagist in his poetics, Christian is also a visual artist. As he tells it, he fell into writing and the urge to make pictures never went away, his medium merely shifted.

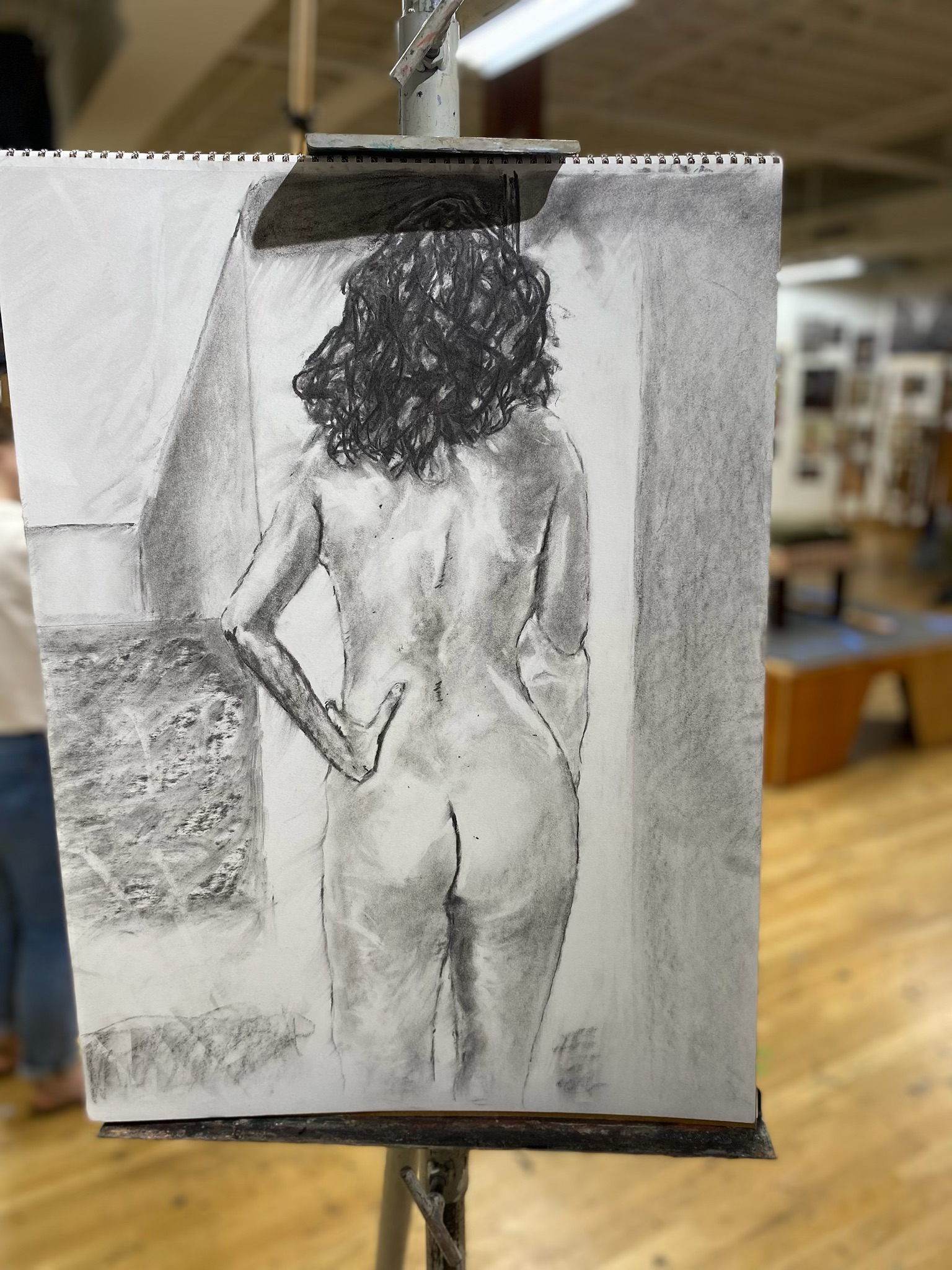

Between the rigor of earning his poetry MFA and the freedom of not yet knowing what’s next, Christian is back in the studio studying figure drawing, polishing a dormant facet of his creative practice. In poetry and in charcoal pencil, Christian renders images that are alive with a desire to connect. His skill, medium aside, is bringing us into the room with the subject.

Although we both call Chattanooga, Tennessee, home, Christian and I met virtually on a humid July evening, he in his home office, and me in my living room, both grateful to be in the comfort of our own air conditioning. We talked about what drawing is doing for Christian, what made him pursue his MFA, ideas and books he picked up during grad studies, his perennial advice for writers, and where he is now as an artist in between one milestone and the next great unknown.

LD: You’re taking a figure-drawing class—sounds like an exciting challenge. Thank you again for sharing some fresh work to feature here. Do you find that studying different art forms feeds your writing, or is this class simply providing a fresh creative outlet?

CJC: The class is really serving as a new creative outlet. However, I’m of the mind that everything informs the sum. Being able to look deeply and really see is so vital to drawing, and I think that act of committed noticing can do nothing but help my writing, especially when it comes to putting detail down on the page.

LD: In an interview with Joy Priest you said that, "intimacy is one of [your] few obsessions." That you, "want to put the reader as close to what's happening as possible." What are your other obsessions?

CJC: I realize, thanks in part to my figure drawing class, just how long I’ve been obsessed with the body. Grace has been a recent obsession, and it’s one that permeates through my thesis poems.

LD: Do you see your drawing and writing worlds colliding in the near (or far) future?

CJC: I once wanted to write and illustrate my own comics. Then I just wanted to do visual art, then writing happened, and I decided to just do more of that. But every now and then I try to shake the rust off, then get busy with writing again. I play music, write, make visual art, etc., but I’ve never really been able to reconcile the different art forms I practice. My friend mentioned that I should try to incorporate some of my drawings into a future body of work, and I would be open to that, but it has to happen in a way that both makes sense and serves the work. I’m still quite a ways off from any of that, just excited to shake that rust off once more, see what’s next, and to be able to access different versions of myself.

LD: I’ve seen you in this home office before — are you someone who needs to be in a specific space to work?

CJC: When I was in my last fiction class I would write in this office because it gave me the chance to get away from everything and commit to inhabiting the space that I was making. But for probably the past two years while I've been doing the grad school thing, I’ve been primarily writing more in shared space with my wife. Because so much of the focus during grad school was deadline driven, things had to be done pretty fast. So I constantly had to work because I’m a slow writer, typically. At least when it comes to poetry. Then most of my editing takes place after my wife goes to bed. I need to be alone for that process, where I’m asking questions of how to push things farther along or how to deepen them. I like getting into that quiet space where I'm hearing things at their loudest volume on the page, seeing the gaps, the blind spots. All of those things become more prevalent when I'm able to immerse myself in that way. Even in terms of arrangement, ordering poems. I did two arrangements of my thesis. The first one, I did what I usually do, which is print and lay out all the poems, so I have to use a space that's big enough to do that. I used pretty much the entirety of my downstairs. I laid the poems out on every surface then kind of bounce back and forth thematically from pile to pile. Then the last arrangement I did at my sister's house. So writing location doesn't really factor in as much as being able to pick a starting point. I know where I ultimately want to go, then work my way, weaving and braiding to push myself through the work.

LD: To ground our conversation in time, what’s bringing you joy right now?

Some of the things that are bringing me joy are having a new cohort from grad school. That’s been really unexpected but very neat. I realized that's something that I have longed for, in a way, for a long time now. It feels exciting in a way that I don't know if I’ve felt before.

I'm also happy about this new body of work that I made for my thesis, which I will manipulate more. Doing that work really brought me more into my own and made me trust myself and my instincts and what I'm after as an artist. I'm appreciative of being able to recognize that. These things are bringing me joy.

LD: So you intend to work on your thesis more. How do you feel about where it stands?

CJC: If any of these things are ever really complete, I think it's pretty close to that. It’s talking to the poems from my chapbook in different ways. So it has completely recontextualized that work.

LD: Your thesis work is in conversation with your chapbook, The Gleaming of the Blade, not with your latest poetry collection Greater Ghost?

CJC: Yes. So I'm of the mind that once you change one thing in a series or a collection, you in a way change everything. Like the butterfly effect to some degree.

A lot of the thesis deals with coming of age. It's hitting at different things in terms of people I knew and grew up with, people who were very flawed individuals. The boys and young men that I came up with, even though a good number of us had fathers, we in some ways fathered each other through the charge of masculinity and what was acceptable. And so what does it mean when you have flawed individuals fathering and parenting other flawed individuals, the damage that comes with that.

LD: Tell me more about how your new work functions differently from your previous work.

CJC: I was in a place where I didn't want to feel like I'd said everything I wanted to say or could say about race in the chapbook. I kind of exhausted the whole thing about ghosts in the full length, and so I wanted to find, as Jorie Graham mentions, the new music.

Hixson, Tennessee is where I grew up — my current house sits maybe five minutes from the high school I graduated from. Moving back to this exact place in 2022 brought back memories of people I knew in different times, and different selves. And it brought me back to different things that have haunted me in different ways, different flaws, things I've really tried to look past. I felt that if I wanted to make something as honest as it could be, then I really had to not just look at this place, but really get into cracking those things open in this place. What is it like to try to understand and inhabit beauty in a place that, for a long time, you never felt was capable of seeing you as beautiful? I'm looking at intimacy in terms of living here. And how often that meant being either invisible or overlooked, and then as a man, being put in different boxes to be something kind of beautiful, or you know, being a bull for a couple1, right, things of that nature. I have felt ugly for a lot of my life, but I've also felt very ugly here. This is the epicenter of that feeling. So I had to face that. [My thesis] is the most personal work that I've ever made. And as a result it's the bravest work in a lot of different ways.

This has been written about so it’s not a spoiler, but a lot of Greater Ghost deals with a miscarriage. In that work, I took a real thing and turned it around a little bit so that it became part of a narrative that played itself out. I'm not doing that this time. I'm really attacking it head on. There's a poem in the chapbook about being driven out of Graysville after a lover's father has threatened to blow the speaker’s head off. That's real. And there's a poem in the thesis that basically says, that guy has passed on, and the poem's like, I'm glad that you're dead. But that's the easy work. The easy thing is saying that. The harder thing is to get behind that. And it's like, well, why? The poem says, it's because you cannot harm anyone or anything else Black ever again. That is the truest part of the poem.

What is it like to try to understand and inhabit beauty in a place that, for a long time, you never felt was capable of seeing you as beautiful?

There are also a lot of formal poems in this work. Some traditional, one ghazal, a good number of nonce forms, contemporary forms, newer things. A poet named Chad Bennett created a form, Ten discrete lines: Four repeated. I return to that a lot because it gives you notes of sonnet and notes of narrative, but it really denies you both. I think this work has allowed me to establish myself more as a formal poet. I also think these poems still have my signature. You can identify that I wrote them, but they're also showing you what else I can do.

LD: You talk a lot about permissions in your work. What permission has your thesis work given you?

One of the principal texts for my newer work is The Poetics of Wrongness by Rachel Zucker. I’ve been preaching the gospel of that to everybody. Even if you don't write poetry, there are gems dropped throughout it. I cannot recommend it enough. It just really allowed me to interrogate my poetics and to challenge them in different ways. That book gave me so many permissions to stake my claim as a writer. I’ve been in the trenches for a long time. Sometimes you’ve got to strut a little bit. And that book has allowed me to step into that and strut some.

LD: What else is widening your aperture lately? Other books, etc.?

CJC: There’s a collection, How We Do It: Black Writers on Craft, Practice, and Skill, edited by Jericho Brown. Different essays on topics like lineage, and Evie Shockley has a piece on Black experimental art, things like that. The book lets you know that regardless of where you fall on the map, you’re part of a tradition. Beyond that, two of Carl Phillips’ craft books have really come in handy, I don't think that you can ever go wrong with anything that Carl Phillips is a part of.

When I took my first fiction class for the grad studies, I got some very positive feedback on my work. But back in undergrad, a different professor encouraged me to focus on poetry, and so I didn’t touch fiction for almost 20 years. And in a way that really robbed me of cementing that self. But now I see that’s also a possibility. And a similar thing happened with my nonfiction, like there’s a place for you here, where you don’t sound like Damon Young or you don’t sound like Kiese Laymon, but there’s a lane for you if you want it, you have that space. It’s allowed me to see myself as what I think I’d always dreamt of being, which is a well-rounded writer, period. Not just a poet, but a good writer. So I’m excited about leaning more into all of that. Expanding what I have the capacity to do as a maker of things.

LD: Any advice for other writers who have also hidden a specific genre of their work in a drawer for years because of a comment someone made?

CJC: In whatever way you can, try to keep the making of the work as pure a space as possible. You don't want somebody to taint the thing that you feel you can do well but also enjoy doing and have formed a self around doing. You want to try to keep that space as sacred as possible.

I feel so blessed that, being older, having acquired the grit that I have, no matter what any person in the grad program said or did or whatever, it was always going to remain pure with me. Because I've fought so hard to stay here—I sound like a guy from Chicago, ha—and you're not moving me from my square. I've worked so hard to hold this space, so this is going to remain a sacred space.

Maybe you take a workshop with somebody who changes that energy or changes the way that they see it, but somehow, you’ve got to get that badness out of it. Also, it’s going to sound so simple, but you’ve got to stay in the dojo. If you want to write, you’ve got to show yourself that you want to write. And it's more than just putting words on the page. Not only read broadly. You can find good stuff in podcasts. If you write short stories, Deesha Philyaw and Kiese Laymon have a really good podcast focused on writing. You can get great craft stuff on YouTube. If you can't afford to go to a workshop or conference, maybe they have craft lectures you can access for free. That way you’re adding things to your skillset and your knowledge base that, once you apply them, can amplify what you're already doing to make your dreams move a little bit closer to your grasp. There's so much beyond just the making of the work that goes into making the work solid.

I try to influence people to work on your voice, your signatures. No computer or software or other humans can write like you. ChatGPT can’t write like George Saunders because other human beings don’t write like George Saunders.

LD: What pushed you over the edge to get your MFA?

CJC: I was doing a program with a university, and a couple members of the faculty approached me like, “Hey, we really like you and we would really like to work with you, but you have to get your MFA.” And that happened to come at the right time, where I was open to it. For a long time I didn’t want to have anything to do with academia. Academia really failed me in some big ways. But for whatever reason at the end of 2022, I was like, you know, that might not be the worst thing. So I spent about a month doing the internal work to make sure I was ok jumping back into this space and ultimately decided to go for it.

Vievee Francis told me once a couple of years ago that the goal of grad school is not to make the poet, but to hone the poet. And I think that’s really important to have in mind if you’re looking to apply. You have to be clear on what you’re hoping to do and get out of the experience. If you’re just expecting that, no matter where you go, this thing is going to automatically make you the best writerly version of yourself, you’re setting yourself up for disappointment. It definitely can help you. But you still have to stay in the dojo. And you have to figure out how you can not only make this work better, but how can you make it the best that it can be? Not for the program, but for you beyond the program. This is the program of life we’re talking about. That means the work you do inside and outside of class is equally important. It’s your responsibility to try to make your dreams come true.

LD: Ok, here it comes. What’s your take on AI?

CJC: I know we’ve had some ongoing discussions about artificial intelligence, do we need to worry, and should people use it, stuff like that. This definitely popped up in a couple of ways during my last residency for grad school. Bottom line, it’s not going anywhere, that’s just the reality. Whether you’re somebody who wants to use it for everything or not use it at all, you at least should have working knowledge, know how it works. The reality is that, at least ChatGPT is capable of writing OK prose, but there are also a lot of human beings who write OK prose, right? So in whatever capacity I can, I try to influence people to work on your voice, your signatures. No computer or software or other humans can write like you. ChatGPT can’t write like George Saunders because other human beings don’t write like George Saunders. There’s a reason why George Saunders is George Saunders. Once you start looking at it like what makes Raymond Carver Raymond Carver, and Hemingway Hemingway, you can start to get into the same coliseum, but it’s not the same. And that’s what we should all be shooting for regardless of if we have technology that is generating text or not. You want to have something that’s so distinctly yours that we can recognize something that’s hinting at it, but still can’t touch it. Strive for that. Strive for finding the distinct things that make you and your work what they are.

—

Classes to sharpen your voice during the final days of summer 2025:

Sept. 3-24 — Whether you want to try making pictures with words or you already do, join Writing Poetry for Beginners with Christian Detisch (4 weeks / online / wednesday evenings)

Sept. 5 — Bring your readers closer to nature. Learn how with Melissa Jean in Write Like a Naturalist

Sept. 8-29 — Make your story shine from start to finish. The Hero’s Journey: A Story Structure Workshop with Silk Jazmyne (4 weeks / online / monday evenings)

Sept. 15 — Invite music into your writing life. Put the Needle on the Record: On Writing & Music with Vanessa Martir